TREATMENTS

Some acute and many preventive migraine treatments are non-specific, and their effectiveness, safety, and tolerability may be suboptimal.1 Ergot alkaloids and methysergide were introduced in the 1940s as the first migraine-specific types of medications. This was followed by the advent of dihydroergotamine (DHE) in the 1950s and the triptans in the 1990s, both of which act by blocking the release of CGRP and glutamate.2 Recent research has focused on the role of neuropeptides in the pathophysiology of migraine, with the subsequent development of agents blocking their activity as a new strategy.

Therapies for migraine are acute or preventive. The goal of acute medications is to abort an attack. Preventive medication are designed to reduce the frequency and intensity of attacks.1

Optimization of migraine therapy includes early treatment of an acute attack (early recognition and rapid therapy), prevention through identifying and eliminating exacerbating factors (reducing attack frequency, severity, and disability), continuity of care, improving patients’ quality of life and ability to function, treating comorbidities, minimizing adverse events, avoiding medication overuse, and improving patient education (realistic expectations and how to manage migraine and increase patient control including trigger identification and avoidance).2,3

Evidence-based approaches to managing acute episodes of migraine and for preventing recurrent episodic and chronic migraine have recently been summarized and reviewed, including treatment in primary care3 and emergency department (ED)4,5 settings. There is no definitive approach for patient-specific care,6 as the most appropriate plan will depend upon factors such as:

- Comorbidities, including asthma, psychiatric diseases (depression, anxiety, and others), restless legs syndrome, epilepsy, coronary heart disease, hypertension, patent foramen ovale, and obesity7

- Type of migraine, based on precipitating factors (menstrual migraine)3

- Severity of symptoms3

- Pregnancy (risk of teratogenicity) or breastfeeding3

- Medication risks/side effects and potential drug interactions3

- Associated significant nausea, vomiting, or gastric paresis3

- Risk of dependence3

Treatment of acute migraine

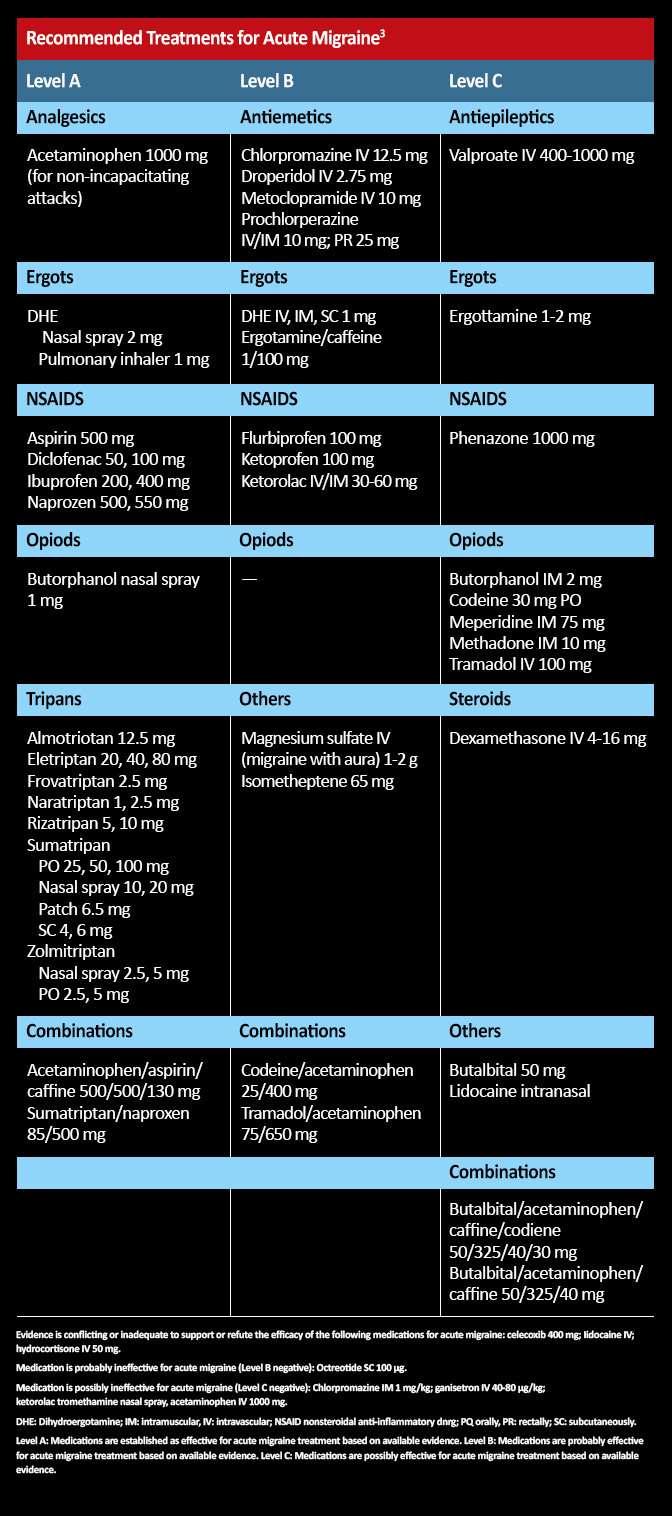

Evidence supports the therapeutic value of several treatments for acute migraine.6 Medication classes that have been proven to be efficacious include triptans, non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), ergots, and certain combination therapies.3,6 Triptans and NSAIDs constitute the main therapies for acute migraine, together with an antiemetic as indicated.3

In general, the initial management of acute attacks of mild-to-moderate severity includes NSAIDs. Triptans are useful where there is a severe attack or a moderately severe attack unresponsive to NSAIDs; they usually exhibit a good benefit-to-side-effect ratio.3 The response to triptan therapy varies by patient, with individual triptans producing a good therapeutic response for some patients but not for others. Table 1 outlines recommended treatments for acute migraine, stratified by the level of evidence supporting their use.3 Combining triptans and NSAIDs can be a helpful therapeutic approach for patients who are unresponsive to single-medication therapy. More complex lines of therapy can be reserved for when a patient’s usual medication proves to be ineffective.3

Table 1. Recommended treatments for acute migraine. 3

There are several potential strategies for migraine when vasoconstrictive agents are contraindicated. These includes NSAIDs and combination analgesics.3 The safest approach during pregnancy is acetaminophen.8 Single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation is a promising evidence-based therapy that is FDA-approved for the acute and preventive treatment of migraine.8 Alternate modes of administration have been developed for some medications. Triptans are available as oral, subcutaneous, and nasal spray formulations. There is a DHE inhaler, a sumatriptan nasal powder, and a zolmitriptan oral inhaler or patch. These newer formulations afford more flexibility in managing patients where there is a concern about the effectiveness of therapy or in the presence of significant nausea, vomiting, or gastroparesis that could impede the intake or delay the absorption of oral medication.8

Important points in the management of an acute migraine attack include3:

- Commence therapy early (medication will be more effective).

- Consider combining two or more acute medications where indicated.

- Tailor medication to the specific patient’s presentation (eg, severity, other clinical features, risks, comorbidities)

- Flexibility—adapt the approach to patient response; initial regimens may not be effective.

- Employ non-tablet formulations for medication delivery where there is gastric paresis or significant nausea/vomiting. Options include wafers, transdermal administration, nasal powders, sprays, and injections.

- Avoid overuse of acute medication.

- Avoid the routine use of opiates; they can lead to an accelerated frequency of use and medication-overuse headaches.

Recent reviews have summarized evidence-based and comprehensive approaches to acute migraine treatment in the ED.4,5 Studies suggest that migraine-specific medications are used in less than half of ED cases and that opioids are frequently prescribed despite recommendations that they should not be a routine first-line of therapy.4,5 A plan for care following discharge from the ED is essential.5

Agents in development for acute migraine include several gepants and the 5-HT1f agonist lasmiditan, which is currently under review for FDA approval. New formulations in development include microneedle-array skin patches (zolmitriptan and sumatriptan), orally inhaled agents (zolmitriptan and DHE), and intranasal delivery (sumatriptan liquid spray with enhanced permeation).

Treatment of chronic and frequent episodic migraine

Chronic migraine sufferers benefit from a comprehensive management plan and a team-based approach. Such an approach results in a greater likelihood of optimal headache care.3,10,11 PCPs are the first-line of care for migraineurs, and they will usually continue to manage sufferers between specialist visits and after neurologist/headache-specialist consultation.11 Their role includes making a clinical diagnosis, identifying red flags for secondary causes of a headache, prescribing therapy for acute migraine, and referral to a specialist where appropriate.

Additional management steps include treating comorbidities (eg, anxiety and depression),12 commencing a wellness program (ie, exercise, good nutrition, adequate sleep, smoking cessation, and achieving a normal body mass index), and considering prophylactic medication where appropriate. Migraineurs may require psychological and psychiatric support, including cognitive-based therapy. Adequacy of care can be evaluated by encouraging patients to complete a Migraine Treatment Optimization Questionnaire (M-TOQ).13

| Assessing Unmet Treatment Needs13

5-question Migraine Treatment Optimization Questionnaire (M-TOQ-5) |

|

| Domain | Yes or no questions |

| Functional response | Are you able to quickly return to your normal activities after taking your migraine medication? |

| Consistency and onset | Can you count on your migraine medication to relieve your pain within 2 hours for most attacks? |

| Recurrence | Does one dose of your migraine medication usually relieve your headache and keep it away for at least 24 hours? |

| Side effects | Is your migraine medication well tolerated? |

| Global | Are you comfortable enough with your migraine medication to be able to plan your daily activities? |

Prevention

The threshold for preventive medication is 5 or more migraine days per month or less frequent attacks that have a significant impact on quality of life.14 Agents traditionally employed for migraine prevention were developed for other clinical indications. These include anticonvulsants, beta blockers, angiotensin modulators, calcium channel antagonists, and a range of natural therapies.14–16

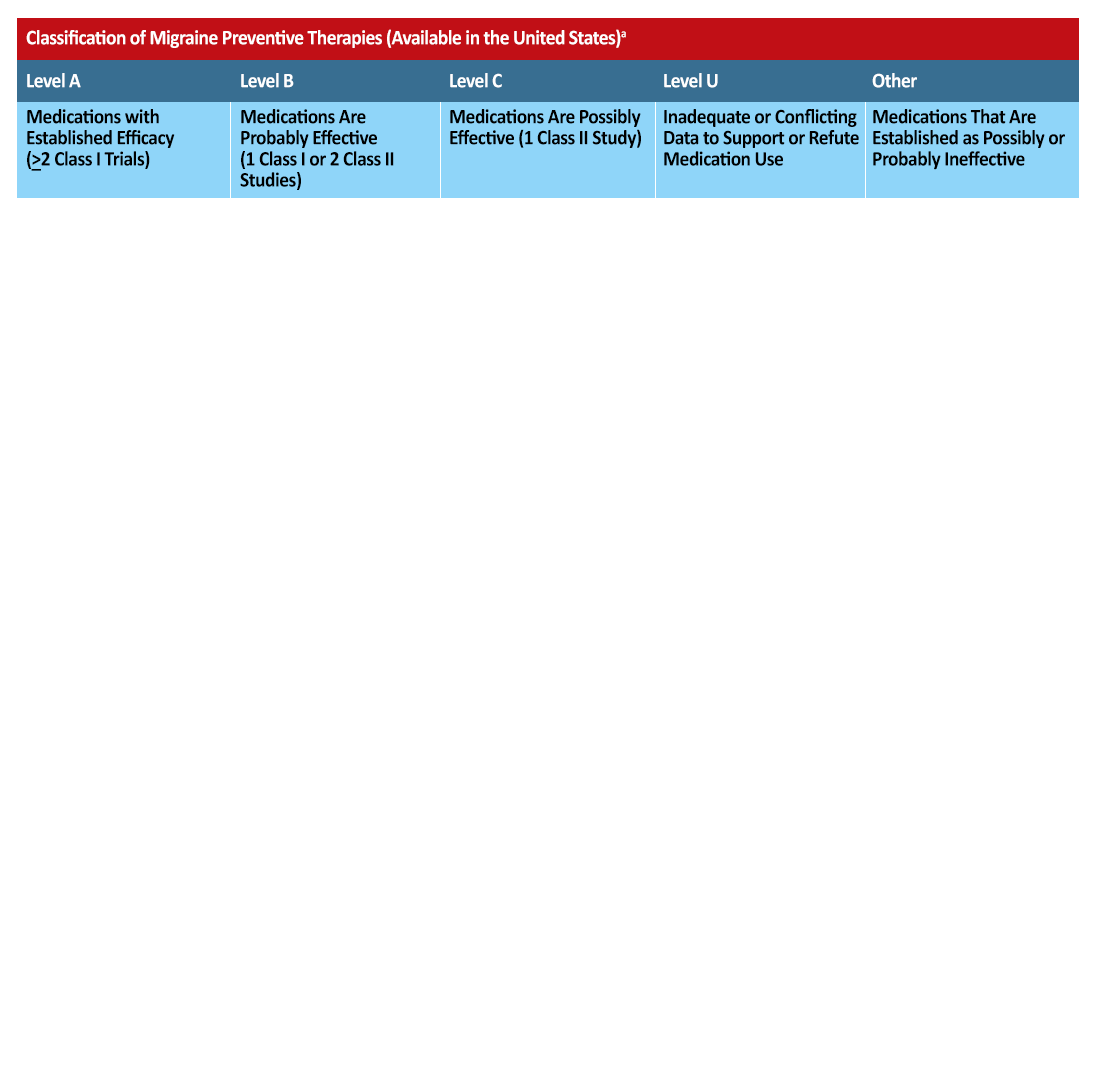

Table 2 outlines prophylactic medication available in the United States by level of evidence regarding efficacy. There is strong evidence that the following beta blockers (metoprolol, timolol, propranolol), and anticonvulsants (divalproex sodium, sodium valproate, topiramate) are effective as assessed by the American Academy of Neurology.15

Table 2 Migraine Preventative Therapies Available in United States.17,18

Additional prophylactic measures can include botulinum toxin,19 and neurostimulation. Supraorbital external trigeminal nerve stimulation and single pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation are both approved by the FDA for the prevention of migraine headaches.20,21 As with the management of acute migraine, patient-specific factors such as comorbidities dictate the best approach. For example, beta blockers can lead to deterioration in depression, and they may be contraindicated in asthma.3

Migraines improve for about 70% of women during pregnancy,14 and prophylaxis should be used with caution in pregnancy due to the risk of teratogenicity. Menstrual migraine (usually without aura) is thought to be associated with cyclical variations in reproductive hormone levels.21 Potential therapeutic approaches include perimenstrual “mini-prophylaxis” \and amenorrhoea induced by continuous contraceptive pill use.14

New treatment options

Absent from the table above are newly-released calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antagonists. CGRP is a neuropeptide which is a component of migraine pathophysiology and may prove to be a marker for chronic migraine.1,23,24 CGRP-receptor antagonists (gepants) showed promise in the treatment of acute migraine, but initial research efforts ceased after adverse events such as hepatotoxicity were reported.24

New research has focused on migraine prevention through the development of monoclonal antibodies that target either CGRP or its receptor.1,23,24 Unlike gepants, CGRP monoclonal antibodies are parenteral medications that have not been found to be associated with hepatotoxicity and have a very long half-life.1,23 As CGRP monoclonal antibodies are macromolecules, they do not cross the blood-brain barrier in significant quantities.1,23 As a result, their sites of action are mainly peripheral, including at the level of intracranial vessels, extracranial vessels, dural mast cells, and the trigeminal ganglia.1

Currently, there are three CGRP agents FDA-approved for migraine prevention:

- Erenumab: (acts at the CGRP receptor)

- Fremanezumab and galcanezumab (act directly against CGRP)

Another agent – eptinezumab is in Phase III clinical trials, and has shown promising results.

Patient education

Patient education is an important component of PCP management, 2,3,10,11,25,26 focusing on:

- Approaches to prevention

- What to do when there are prodromal symptoms and at headache onset

- Medication side effects

- Encouraging medication compliance

- Educating patients about realistic expectations for symptom reduction, ie, that symptoms will improve over time

- Encouraging patient to keep a headache diary to monitor therapeutic response and compliance, identify medication overuse, and detect triggers

- Modifiable exacerbating factors and their role in prevention, such as excessive caffeine, skipped meals, and contributory sleep pattern

- Trigger identification and avoidance where possible

- Travel, pregnancy, and stressful events

- Red flags and what to do if treatment is not working

Cluster headache

Rapid acting abortive agents are needed in the treatment of cluster headache to reduce the severe pain that peaks quickly during an attack.27 Therapeutic approaches that are most commonly utilized for acute attacks are inhalation of 100% oxygen via a non-rebreathing face mask and sumatriptan injections. First-line prophylactic agents include verapamil, carbolithium, and short-term corticosteroids.27 Monoclonal antibodies against CGRP are currently being investigated as prophylactic agents for both episodic and chronic cluster headaches. Neurostimulation may be indicated when pharmacological options have failed. A noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation device (gammaCore®) has recently been approved by the FDA for the treatment of pain from episodic cluster headache.27

References

- Giamberardino MA, Affaitati G, Curto M, et al. Anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies in migraine: current perspectives. Intern Emerg Med. 2016;11:1045-1057.

- Dougherty C, Silberstein SD. Providing care for patients with chronic migraine: diagnosis, treatment, and management. Pain Pract. 2015;15:688-692.

- Silberstein SD. Considerations for management of migraine symptoms in the primary care setting. Postgrad Med. 2016;128:523-537.

- Saguil A, Lax JW. Acute migraine treatment in emergency settings. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:742-744.

- Orr SL, Friedman BW, Christie S, et al. Management of adults with acute migraine in the emergency department: the American Headache Society evidence assessment of parenteral pharmacotherapies. Headache. 2016;56:911-940.

- Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD, Schwedt TJ. The acute treatment of migraine in adults: the American Headache Society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies. Headache. 2015;55:3-20.

- Wang SJ, Chen PK, Fuh JL. Comorbidities of migraine. Front Neurol. 2010;1:16.

- Becker WJ. Acute migraine treatment. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2015;21 (4 headache):953-972.

- Lipton RB, Dodick DW, Silberstein SD, et al. Single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation for acute treatment of migraine with aura: a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, sham-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:373-380.

- Nicol AL, Hammond N, Doran SV. Interdisciplinary management of headache disorders. Techniques Reg Anesth Pain Manag. 2013;17:174-187.

- Starling AJ, Dodick DW. Best practices for patients with chronic migraine: burden, diagnosis, and management in primary care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:408-414.

- Minen MT, Loder E, Tishler L, Silbersweig D. Migraine diagnosis and treatment: a knowledge and needs assessment among primary care providers. Cephalalgia. 2016;36:358-370.

- Lipton RB, Kolodner K, Bigal ME, et al. Validity and reliability of the Migraine-Treatment Optimization Questionnaire. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:751-759.

- Sinclair AJ, Sturrock A, Davies B, Matharu M. Headache management: pharmacological approaches. Pract Neurol. 2015;15:411-423.

- Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

- Loder E, Burch R, Rizzoli P. The 2012 AHS/AAN guidelines for prevention of episodic migraine: a summary and comparison with other recent clinical practice guidelines. Headache. 2012;52:930-945.

- Silberstein SD. Preventive migraine treatment. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2015;21(4):973–989.

- Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

- Wilkes J. AAN updates guidelines on the uses of botulinum neurotoxin. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95:198-199.

- Magis D, Sava S, d’Elia TS, et al. Safety and patients’ satisfaction of transcutaneous supraorbital neurostimulation (tSNS) with the Cefaly® device in headache treatment: a survey of 2,313 headache sufferers in the general population. J Headache Pain. 2013;14:95.

- Schoenen J, Vandersmissen B, Jeangette S, et al. Migraine prevention with a supraorbital transcutaneous stimulator: a randomized controlled trial. 2013;80:697-704.

- Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Chee E, et al. Menstrual cycle and headache in a population sample of migraineurs. Neurology. 2000;55:1517-1523.

- Freitag FG, Shumate D. Current and investigational drugs for the prevention of migraine in adults and children. CNS Drugs. 2014;28:921-927.

- Bigal ME, Walter S, Rapoport AM. Therapeutic antibodies against CGRP or its receptor. Br Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79:886-895.

- Pringsheim T, Davenport WJ, Marmura MJ, et al. How to apply the AHS evidence assessment of the acute treatment of migraine in adults to your patient with migraine. Headache. 2016;56:1194-1200.

- Schuster NM, Rapoport AM. New strategies for the treatment and prevention of primary headache disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:635-650.

- Leone M, Giustiniani A, Cecchini AP. Cluster headache: present and future therapy. Neurol Sci. 2017; 38(S1):45–50.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)